Entomology Research Museum U.C. Riverside

A place to wonder and marvel at the unique life histories of the arthropod fauna. Enjoy the graphical descriptions including close-up shots and video clips of insects and other arthropods.

Here are the latest arrivals:

(click a card to see more)

Caterpillar

Description of Insect

Caterpillar

Description of Insect

Tomato hornworm

Description of Insect

Caterpillar

Description of Insect

Caterpillar

Description of Insect

Caterpillar

Description of Insect

Caterpillar

Description of Insect

Dragonfly

This is a closeup of the head and thorax of a Green Darner dragonfly (Anax junius). Dragonflies and their relatives, the damselflies, comprise the insect Order Odonata, all of which are characterized by their predatory aquatic immature stages ("naiads"), and distinctive, archaic types of wing venation, musculature and flight mechanism. Unlike most other insects, the wing muscles of dragonflies insert directly at the wing bases, which are hinged so that a small movement of the wing base downward lifts the wing itself upwards. Even though dragonflies cannot hover with this primitive mechanism (they can "cheat," though, with careful use of wind currents), damselflies can, and in both groups, the fore and hind wings are operated independently, which gives a degree of fine control and mobility not seen in other flying insects; not surprising given that these aerial predators have been terrorizing other airborne insects since before the dinosaurs - if they couldn't outmaneuver their prey, they would have gone extinct long ago. This flight mechanism also gives the lie to one of the well-promoted "mosquito repeller" scams (ALL mosquito repellers are scams, for various reasons). In this case, it's the type where the manufacturers claim that their device replicates the wingbeat frequency of a dragonfly (which supposedly scares the mosquitoes away): since dragonfly wing muscles insert directly, they do not HAVE a constant wingbeat frequency - their wingbeat speed can vary at random, like a bird, and not necessarily even in a rhythmic pattern.

Wasp

Description of Insect

Parasitoid

Description of Insect

Caterpillar

Description of Insect

Wasp

Description of Insect

Hornet Wasp

Description of Insect

Walkingstick

Description of Insect

Paper wasp

Description of Insect

Orthoptera

Description of Insect

Butterfly

Description of Insect

Monarch caterpillar

Description of Insect

Grasshopper

Description of Insect

Solpugid

Sunspider...

Carpenter bee

Description of Insect

Lynx spider

Hunting, waiting for prey on top of flowers.

Blue Dasher Male

(Pachydiplax longipennis)

Resting...

Diptera

Panthophthalmid Fly, Panthophthalmus bellardi

(Diptera: Brachycera: Pantophthalmidae) by Doug Yanega.

Pantophthalmidae is a small family of giant flies. There are only 22 species in the family, all of them Neotropical, and while they resemble Horse Flies (Tabanidae) they are only somewhat related to them, and do not bite. In fact, the adults don't feed at all, spending most of their lives as large grubs boring in trees, especially in roots, so the adult stage is only a very brief portion of the life cycle, similar to cicadas. There is at least one species, Pantophthalmus roseni, which is a minor pest, attacking oaks in Mexico , apparently boring into various parts of the living tree. Adult females of this family, such as the one shown on the left (male on the right), can reach two inches in length, which makes them the second-largest living flies (only a few species of Mydas flies are larger). A few species are mimics of Tarantula Hawk Wasps (Pompilidae, genus Pepsis). The species shown here, Pantophthalmus bellardi, occurs throughout Central America south to Peru and Brazil, and the specimens in the photo are from Pico Pijol National Park in Honduras, where they fly for only a short time, exactly at dusk, sometimes enticing enthusiastic but careless entomologists to get tangled in the vegetation and break their ankles, as these specimens did.

Bolas Spider, Mastophora species

(Arachnida: Araneidae) by Rick Vetter

The bolas spider genus Mastophora includes 15 species in the United States with only one, M. cornigera, found in California (the genus was recently re-revised). Bolas spiders are not common or at least not commonly collected. In part, they hide during the day and are cryptic, looking very much like a bird dropping (figure top left, spider from California) with light streaks mimicking the uric acid found in bird feces. Most bolas spiders are found by first locating their black and white mottled egg sacs (figure bottom left). Although bolas spiders are in the orb-weaver family Araneidae, they have evolved away from making a large orb web of silk for hunting. Instead, they produce just a single droplet of sticky silk, which they suspend at the bottom of a dragline (figure on right, spider from Kentucky ).

How could they possibly catch much prey by just suspending a little sticky ball of silk? Many years ago, it was determined that the prey of bolas spiders were very unique: male noctuid moths of only a few species. How is the spider selectively preying on only a few male noctuids? The female bolas spider sits out at night emitting the sex pheromone of female moths. Male moths fly up to her thinking that they might get a chance to mate; when the bolas spider senses the air vibrations of the approaching moth’s wings, she swings her sticky globule of silk around, strikes the male moth and reels him in. Of course, baby bolas spiders are too small to catch large noctuid moths and for years it was a mystery what they ate. Finally it was determined their prey were humpbacked flies (Phoridae), but only male phorid flies, so the babies are doing something very interesting with sex pheromones as well. Also, male bolas spiders emerge from their egg sacs as penultimates, meaning that they only go through one molt before they mature and therefore are very small in comparison to their female counterparts. Finally, because of the bolas spiders’ ability to twirl its silk, one species in Central America was named Mastophora dizzydeani, after the American baseball Hall of Fame pitcher from the 1930s and 1940s.

The Iron Cross Beetle, Tegrodera aloga Skinner

(Coleoptera: Meloidae) by John D. Pinto

The blister beetle genus Tegrodera, sometimes referred to as soldier beetles (though this common name is technically reserved for the family Cantharidae), includes three very similar species confined to Southwestern North America . These large, colorful beetles, found primarily in late Spring and early Summer, often occur in immense feeding and mating aggregations. Tegrodera aloga, illustrated here, ranges throughout much of the Sonoran Desert in western Arizona , extreme southeastern California and northwestern Sonora . Tegrodera erosa LeConte is our local species. It occurs in the dry valleys and hills of cismontane southern California and south into Baja California . It is likely that T. erosa is undergoing considerable retrenchment in southern California as a result of unprecedented urban development of its habitat. The third and northernmost species is T. latecincta Horn, known from the Antelope and Owens valleys. The primary host plant for all Tegrodera species is Eriastrum (Polemoniaceae), a group of low herbaceous annuals. However, all three species also feed readily on alfalfa where agriculture encroaches on natural lands. Recently there has been concern about the threat that Tegrodera-contaminated alfalfa hay poses to livestock, especially horses. As is characteristic of most meloids tested, Tegrodera hemolymph contains cantharidin, a compound toxic to mammals, which the beetles use to deter potential predators.

Although large and conspicuous, virtually nothing is known about the larval biology of Tegrodera. Based on data from related genera we assume that larvae feed on the provisions and immatures of soil-nesting bees. Adult behavior includes certain interesting peculiarities. The name soldier beetle derives from their occasional habit of following one another in single file formation. Their common response to endangerment is the so-called “frightening attitude”. This involves the sudden elevation of the elytra, which exposes the brilliant red abdominal intersegmental membranes, and a simultaneous rapid movement away from the stimulus. It is suggested that such an abrupt appearance of warning coloration and the apparent increase in body size may, at least initially, intimidate potential predators. Male courtship behavior in Tegrodera is unique. The individual illustrated is a male as can be determined by the pair of grooved depressions on its head. During courtship the male and female face each other, and the male grasps the female’s antennae with his own and repeatedly pulls them in and out of his head grooves where a stimulatory compound of some sort is presumably exuded.

Diopsidae

Peltonotus nasutus Arrow

(Family Scarabaeidae, subfamily Dynastinae) by Dave Hawks

Scarab beetles do all sorts of varied and sometimes strange things, including feeding on dung, carrion, dried animal skin, fur and feathers, as well as more pleasant behaviors such as munching leaves or flowers, or sipping nectar. The Peltonotus scarabs that Greg Ballmer collected during his recent trip to Laos are peculiar in terms of behavior, and also in having a very uncertain classification history until June of 2004. These 2 cm long scarabs uniquely form large feeding and mating congregations of dozens of individuals inside and around the spathe of the large and unusual flowers of the aroid genera Amorphophallus and Epipremnum. Amorphophallus famously includes the world’s largest flower, which also may be the world’s smelliest — reportedly producing a terrible odor similar to carrion. Greg says that A. paeoniifolia, the flowers of which are over a foot in diameter, did not have a particularly bad odor.

Peltonotus is restricted to southeast Asia and consists of 19 described species, and was revised earlier this year by Mary Liz Jameson and Kaoru Wada. Peltonotus has confused scarab taxonomists since its description in 1847 in that it possesses characteristics of both the subfamilies Rutelinae and Dynastinae. Jameson and Wada placed it within the Dynastinae in the tribe Cyclocephalini, mostly because members of this tribe (which include the common tan-colored “May Beetles” of the genus Cyclocephala that frequent porch lights in late spring and summer) tend to have enlarged front tarsi in the males. However, because I was able to sequence DNA from Greg’s fresh specimens, I now know that there is indeed very strong support for Peltonotus as a member of the Dynastinae, but it clearly is not a member of the tribe Cyclocephalini. Instead, it is closest to another mostly southeast Asian genus, Parastasia, which, also based on very strong molecular evidence, presently is incorrectly classified as a member of the Rutelinae! Some scarab beetles are very good at fooling taxonomists and their classification still obviously needs a lot of work. And that’s why they’re so exciting!

The White-Lined Sphinx

(Hyles lineata) Order Lepidoptera, Family Sphingidae

Photos and text by Marcella Waggoner

Moths in this family are easily identified because they are large and have a characteristic triangular wing shape. Adults also have an unusually long proboscis that is used to suck nectar from long tube-shaped flowers. The larvae of many species have a spine or horn at the back end and are called hornworms. The White-lined Sphinx Moth (Hyles lineata), is the most common Sphingid in California. Adults have a whitish stripe running the length of the forewing. Larvae are brightly colored and conspicuous, varying in color from yellow to black and sporting yellow lines down the length of the body. The white-lined sphinx moth is especially common in desert areas. In years of low winter rainfall, the white lined sphinx moth may be completely absent. During years of heavy winter rains, when the desert supports a wide variety of annual plants that are food for the larvae, this sporadic species may be very common and can occasionally occur in tremendous numbers. From April to June the conspicuous and brightly colored caterpillars can be seen feeding on the low growing foliage of desert dandelion (Malacothrix), evening primrose (Oenothera sp.), buckwheat (Eriogonum), sand verbena (Abronia) and wishbone bush or wild four o'clock (Mirabilis bigelovii). Depending on the temperature, these active crawlers move from the food plants to the ground freely and are easily spotted. The larvae are evidently distasteful to some bird species that may spend up to fifteen minutes killing and removing the guts before eating a single larvae. Though the larvae generally stay at least partly shaded, they may drop off one plant to feed from the ground or move to another plant. When populations are especially large, the caterpillars can move in great hordes, devouring entire plants and piling up on roadways in slick masses. Adult white-lined sphinx moths feed on nectar while hovering around blossoms. Because of this behavior, they have often been mistaken for hummingbirds. Adults fly only in late spring and summer. White lined sphinx moths and other moths in this family are especially important pollinators of desert plants having large white, fragrant flowers. Two favorites are Jimson weed (Datura meteloides) and primrose (Oenothera sp.) which open their flowers at sunset. Sphinx moths can be found in dune areas, especially in the spring. You may also see them at night when they are drawn to lights. These moths often thump around clumsily before settling down near the light source.

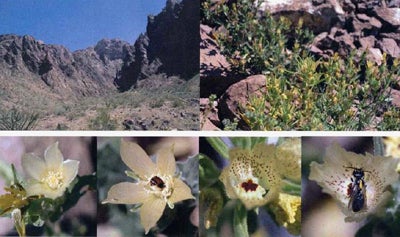

Xeralictus bicuspidariae

(Hymenoptera: Halictidae)

Photos by David Hawks, text by Doug Yanega

In March, 2001, while visiting the Kofa National Wildlife Refuge (upper left photo) south of Quartzsite, Arizona, we discovered a previously unappreciated aspect of a floral mimicry system involving two plants, Mentzelia involucrata (family Loasaceae) and Mohavea confertiflora (family Scrophulariaceae). The two plants are fairly similar in size, shape, and color, and commonly grow in proximity to one another (upper right photo). It has long been recognized that the Mohavea is a mimic of the Mentzelia, as some of the bees that visit the Mentzelia for pollen will also visit the Mohavea, where they cannot collect pollen. In particular, there are two rare species of bees in the genus Xeralictus, one of which, X. bicuspidariae, occurs on the eastern side of the Colorado River, the other on the west. What wasn't recognized previously was that the mimicry of Mohavea involves tricking male Xeralictus into thinking there are females in the flowers. An empty Mentzelia flower is entirely yellow (leftmost lower photo), and patrolling male Xeralictus fly right past them. However, when a female Xeralictus visits the flower, she buries her head in the flower, leaving only the tip of her abdomen exposed amidst the anthers (second lower photo). Patrolling males pounce on females while they're in this vulnerable position, and attempt to mate. The Mohavea flowers have a dark central marking that is almost the exact size and color of a female Xeralictus abdomen (third lower photo). A patrolling male will dive into the flower, but instead of him encountering a female as he obviously expects, the trap-like flower deposits a yellow stripe of pollen on the top of his thorax, where he cannot remove it (rightmost lower photo). The pollen is carried to the next Mohavea flower, so the plant achieves pollination without sacrificing any nectar or pollen to the bees.

Carpenter Bees

Order Hymenoptera Family Apidae, genus Xylocopa

Prepared by Doug Yanega, photos © Rick Vetter

These bees have a tendency to scare people because of their large size and the territorial behavior of the males (which do not sting), which will investigate virtually any moving object within their field of vision. In reality, about the only way to be stung by one is to grab a female in one's hand and squeeze, as they are totally non-aggressive. Females are solitary, each making her own private tunnel into dry wood, where she carves out one to several branches of the tunnel, dividing them into series of "cells" (small chambers set off by partitions made of wood fragments). Into each cell she places a mass of pollen mixed with nectar, upon which she lays a single large egg, which hatches into a larva after she seals the partition. The larvae feed for a few weeks, and then may or may not enter a resting prepupal stage (depending on the species, the climate, and the time of year) before pupating and emerging as an adult after about two weeks as a pupa. In California, the three common species are Xylocopa varipuncta (above), X tabaniformis, and X californica. The first species is most common in Southern California, and has all-black females with bluish wings (with metallic reflections; above, left), but the males are golden-brown (above, right); the second species has smaller black females, and the males are grayish with light faces; the last species resembles a bumblebee somewhat, though the females have darker yellowish hair on the thorax and the abdomen has definite blue or blue-green metallic tints to it. All carpenter bees can be easily differentiated from bumblebees by the relatively bare and shining dorsal surface of the abdomen, and the way they carry the pollen on the entire hind leg, instead of with the pollen concentrated in a single compact mass in a "pollen basket" as in bumblebees. Generally speaking, the damage they do is only cosmetic; it is very rare for them to remove enough wood to cause structural problems.

The Desert Clicker

(Ligurotettix coquilletti) Order Orthoptera: Family Acrididae

By Marcella Waggoner

The desert clicker, Ligurotettix coquilletti, belongs to a group of short-horned grasshoppers called slant-faced grasshoppers (Gomphocerinae). Most slant-faced grasshoppers have distinctive slanting faces, which distinguishes them from most other short-horned grasshoppers. L. coquilletti is dark gray and varies from 18 - 25 mm. in length. Desert clickers are ordinary-looking grasshoppers, cryptically colored to match their background. Hind wings are transparent. Desert clickers are widespread from California to Texas and southward. Like other slant-faced grasshoppers, the desert clicker is usually found in small numbers and has a restricted range of plants on which it feeds. Most commonly, the desert clicker is found on slender gray stems of creosote bush (Larrea tridentata). They can also be found on mesquite (Prosopis spp.), jojoba (Simmondsia chinensis), allscale (Atriplex polycarpa), and sagebrush (Artemisia spp.). Desert clickers get their name from the repetitive acoustic territorial clicking displays (stridulations) of the males. Like other slant-faced grasshoppers, desert clickers have a row of stridulatory pegs on the inside of the hind femur that are used to produce noise. The male's sound is a low tsick-tsick sound that has a ventriloquistic quality and adds to the confusion when trying to find a single clicker. During the summer, males begin singing early in the morning and stop around 11 p.m. Singing is dependent on temperature and may cease early on cooler evenings. Male clickers are very sedentary and spend most of their adult lives in one creosote bush. Although secretive and hard to find, males can sometimes be observed defending an individual creosote bush. The defensive action begins with the adult male signaling his presence with loud stridulations. If these noisy performances do not deter an intruder, defensive behavior will escalate into overt aggressive action with the defending male chasing and fighting the intruder. The three part series of stridulation, chasing, and fighting will be repeated until the intruder wins the territory or is driven away. Females are attracted to the songs of males, but do not sing. Female clickers oviposit in bare soil in open areas away from the plants on which they feed. Eggs undergo diapause (dormancy) during the winter and typically hatch in March or April. Immature clickers undergo five or six nymphal stages. Look for adult desert clickers in May or early June.

Yellowjackets

(Hymenoptera: Vespidae) by Rick Vetter

Although yellowjackets have stocky "bee-like" bodies (upper left), they are indeed wasps. Most wasps are solitary; however, yellow jackets are eusocial, meaning they have a single queen who lays all the eggs and many sterile female workers who do all the work to build the nest and maintain the brood. There are several species of Vespula and Dolichovespula wasps in southern California. Members of the Vespula vulgaris group (V. germanica and V. pensylvanica) are both insectivorous and scavengers; hence, they are nuisance wasps that bother us at picnic tables and attack our pets' food. Other species (V. sulphurea, D. arenaria) are insectivorous only and are beneficial (at least to humans ... but not to bugs). Yellowjackets, like their larger hornet cousins, make a paper nest of dead plant fibers. The foundress queen, working alone in spring, builds a nest in an abandoned rodent burrow (subterranean) or in a tree or under the eave of a home (aerial nest - top right). When the first workers emerge, they take over the foraging and the queen stays in the nest, laying eggs, until she dies in the autumn. In normal situations, the colony grows to about the size of a bowling ball with about 13,000 cells (lower left, as seen through an observation hive at mid-season) and rears males and new queens in the fall. They mate outside of the nest, after which males die and the new queens disperse for the winter, waiting for spring to start the cycle again. On rare occasion however, daughter queens may remain behind in the nest during the winter, 5 to 70 of them start laying eggs the following spring and the nest is referred to as perennial. With many queens laying eggs, the nest can grow to tremendous proportions (lower right). This perennial nest, removed from UCR's Agricultural Operations was estimated to have 200,000 cells.

Velvet Ant

Order Hymenoptera Family Mutillidae

Prepared by Doug Yanega, photos by Greg Ballmer

Velvet Ants are actually a type of parasitic wasp, and the family occurs over most of the world. People are ALWAYS asking about these wasps, especially the eastern US species known as "The CowKiller", Dasymutilla occidentalis. This particular wasp lays its eggs in the nests of the "Cicada-Killer" wasp, Sphecius speciosus (and some other large ground-nesting sphecid wasps) where its larva will eventually eat the cicada-killer larva. Over 450 other species occur in North America, most between 525 mm long. Nearly all of them lay their eggs in the nests of ground-nesting bees and wasps, especially in the Southwestern deserts. Most species are red and black, orange and black, or white and black, but there are other color patterns; for most species this is warning coloration (called "aposematism"), associated with the fact that females (which are always wingless) pack a VERY potent and painful sting. One of the more striking exceptions is one of our Southwest species, Dasymutilla gloriosa (left-hand photo), whose long white hairs apparently mimic creosote bush seeds, so it is actually camouflaged. Some people consider Mutillid stings to be the most painful, but this is always subjective. The males all have wings (righthand photo), and do not sting, as is true of almost all male wasps. Nonetheless, they often have small hooks at the tip of the abdomen which they will jab you with if you handle them. Both males and females also make a sort of chirping-squeaking noise when handled, produced by a special structure called a stridulitrum which is on the upperside of the abdomen, at the junction between two segments.

The Greenest Tiger Beetle

Cicindela tranquebarica viridissima (family Carabidae, subfamily Cicindelinae) by Greg Ballmer and Dave Hawks

Most tiger beetles are fast moving, diurnal predators often found along the shores of rivers, lakes, and estuaries. On warm days, tiger beetles are active and alert, running swiftly and engaging in short low flights in pursuit of insect prey. At night and during cold or inclement weather, tiger beetles seek shelter by burrowing into the soil. Tiger beetle larvae also are predaceous and live in vertical burrows in the soil from which they partially emerge to seize passing insects with their large, sickle-like mandibles. Many tiger beetle species are iridescent or metallic red, green, blue, or purple, while others are plain brown or black. Most species also have whitish markings on their elytra. The Greenest Tiger Beetle is a highly localized subspecies of the widespread species, C. tranquebarica. It occurs only along the Santa Ana River adjacent to Riverside and near Bautista Creek in Hemet . Formerly, the range was much greater, extending along the Santa Ana River from Orange County upstream to Mentone, and possibly along the San Jacinto River as well. Adults emerge in September and October and actively hunt small insects during the warm days of fall. They spend most of the winter underground, and then these same individuals re-emerge to hunt and reproduce during warm days in March, April, and May. As its name implies, this subspecies is just about the brightest green of the many subspecies of C. tranquebarica found throughout most of North America . Other subspecies of C. tranquebarica are green, blue, reddish, brown, or nearly black, and also vary in terms of the whitish patterns on the elytra.